Grano de Oro and Costa Rican Democracy

Frans Lamers

During the 1830’s, when the colonial period ended in Costa Rica, grano de oro became the local nickname for the coffee bean. It was not a derogatory term; to the contrary, it reflected appreciation for having found a unique product that grew well in Costa Rica and for which there was demand on the European markets. Coffee exports allowed for the import of metal tools, such as the crucially important machete. The Costa Ricans could not produce any metal since no iron ore deposits had been located within the country. Initially the economy of the country was completely subsistence oriented. No money circulated as a medium of exchange. The families consumed what they produced, typical for a true peasant economy. Costa Rica had been an isolated, insignificant part of a large Spanish colony established to enrich Spain with gold and silver. During the colonial period only a few Spanish speaking families had settled in Costa Rica; most settled the fertile areas on the Pacific slopes of the volcanoes in the Central Valley

In 1723, when the Irazú volcano erupted and covered Cartago with a layer of ash, it was a town with less than seventy houses. There were no commercial stores, just a church and a chapel. It was the first town and because the first appointed governor was supposed to live there, by default, the capital. Heredia had been established in 1706 and had even fewer houses. All houses were made of adobe and had thatched roofs. San José and Alajuela were founded later, in 1736 and 1782. The founding of a town in the Spanish colonies involved a set pattern, as demanded by the Spanish Crown: a church was to be erected at the center of a street grid, with intersections of 90 degrees. Minimally four streets in each of the cardinal wind directions from the church had to be laid out. The church had to be orientated east/west. The altar needed to face the rising sun in the east, while the entrance needed to face the setting sun in the west. The town square that faced the entrance was to be the central park of the town. Minimal width of streets needed to allow two horse-drawn carts to pass. The length of the blocks was based on traditional Spanish measurements, which in modern terms was equivalent to about 100 meters.

All early towns originated as religious-ceremonial centers since commercial exchanges did not take place yet. The Catholic Church provided the calendar for communal interaction between the newly established farming families. Transition rituals such as marriage, births and deaths were essential to the feeling of well-being as a community. Sundays were the major days for all ages to mingle and visit the park in front of the church for the traditional paseo. Due to the difficult terrain and lack of roads, visits to the other town communities were infrequent. Decisions regarding the building of a church were made by the family elders and the priest, if one was actually present in the community since there was a shortage of priests. A simple and flexible interpretation of Catholicism remained the anchor of otherworldly orientation. The bishop’s see was located in Léon, Nicaragua, but most of the population disregarded decrees from the outside hierarchy.

During the early years of independence, land was available to anyone who would clear a section of the forest. No official bureaucracy existed yet. The few political individuals appointed by the Spanish Crown depended on persuasion rather than giving formal orders. Some families build their houses near the church and walked to their fields. Others cleared land a distance away from the town, since there were few threats from outsiders or bandits. All families, including some who considered themselves “elites of Spanish descent,” had to work the land themselves. No social control mechanisms existed that would allow some individuals to force other individuals to work for them or to monopolize necessary resources, such as water, land, seeds or metals. Only family members were available for labor to produce agricultural products. To ensure basic well-being, the people raised cattle, donkeys, horses, goats, pigs and chickens and planted beans, corn, onions, sugar cane, yuca and several herbs. Farms were located on the Pacific sides of the three major older volcanoes Irazú, Barva and Poas, with their rich volcanic soil, at an elevation between 1000 and 2000 meters. In the rainy/temperate climate of that elevation, the early Costa Rican families started to prosper and families tended to be large due to the high survival rate of usually well-fed children. This population growth led to the continuous westward expansion of new farms from Cartago towards Naranjo.

The Spanish colonial administration was never successful in attracting immigration to the colonies, particularly not to the isolated region of Costa Rica. Thus, at the start of independence, most of the populations of the Central Valley, an estimated 60,000 inhabitants, were descendants of the first settlers of Cartago. They had arrived with Juan Vázquez de Coronado, the officially recognized conquistador of Costa Rica in 1562. He was appointed governor, which allowed him to claim an income from the local families. He died two years later and although his son inherited the title, neither was able to establish government institutions. It was the individual priests and the elders that made sure that the people followed basic Catholic guidelines for proper living, such as the rule against incestuous relations. The early Costa Rican population became closely related since few individuals obtained spouses from outside the country or from the lowland indigenous communities.

Precisely when coffee was first cultivated in Costa Rica is not recorded. Coffee did not originate in the Americas, but in Africa. The roasting of coffee was invented by the Muslim populations of Africa and the first Europeans to import the roasted beans were the Venetian traders. The first Europeans to obtain coffee plants were the Dutch traders of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), who planted them in Ceylon and Java in 1696, breaking the monopoly of the Muslim traders. The Dutch traded un-roasted coffee. That allowed anyone in the tropics to sprout the seeds and start growing a coffee crop. The Dutch West India Company introduced coffee to Suriname and Brazil in the early 1700’s, about the same time the plants started to be cultivated in Santo Domingo/Haiti and Martinique. Unlike in Costa Rica, in most of those regions colonists used slave labor and coffee was merely added to the work of the slaves. The introduction of coffee in Costa Rica did not upset the existing balance in social relations. The farming families adopted coffee as the most valuable item for export. The dried un-toasted beans were not perishable and did not lose their quality during the long arduous voyage to Europe.

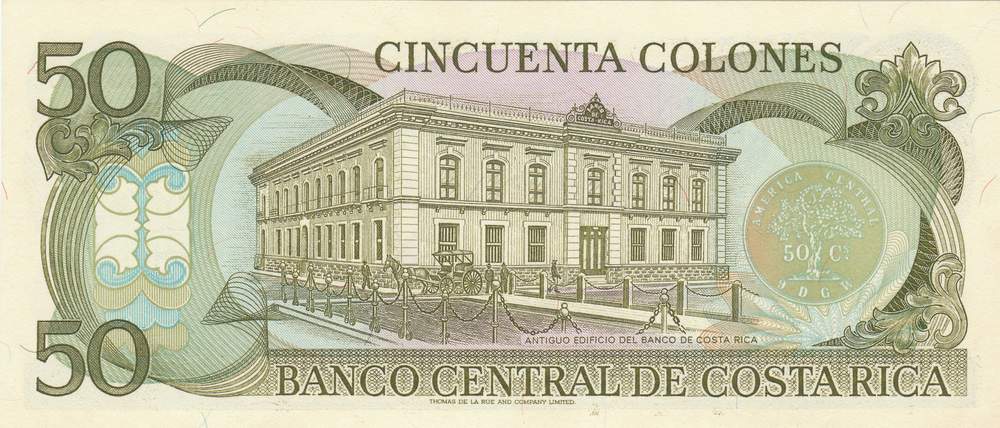

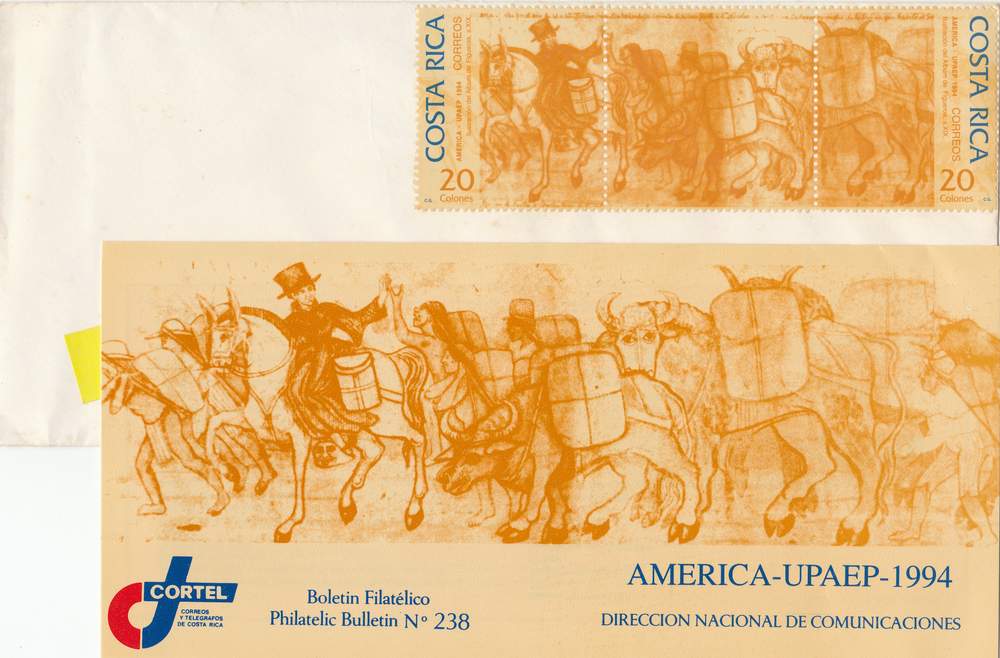

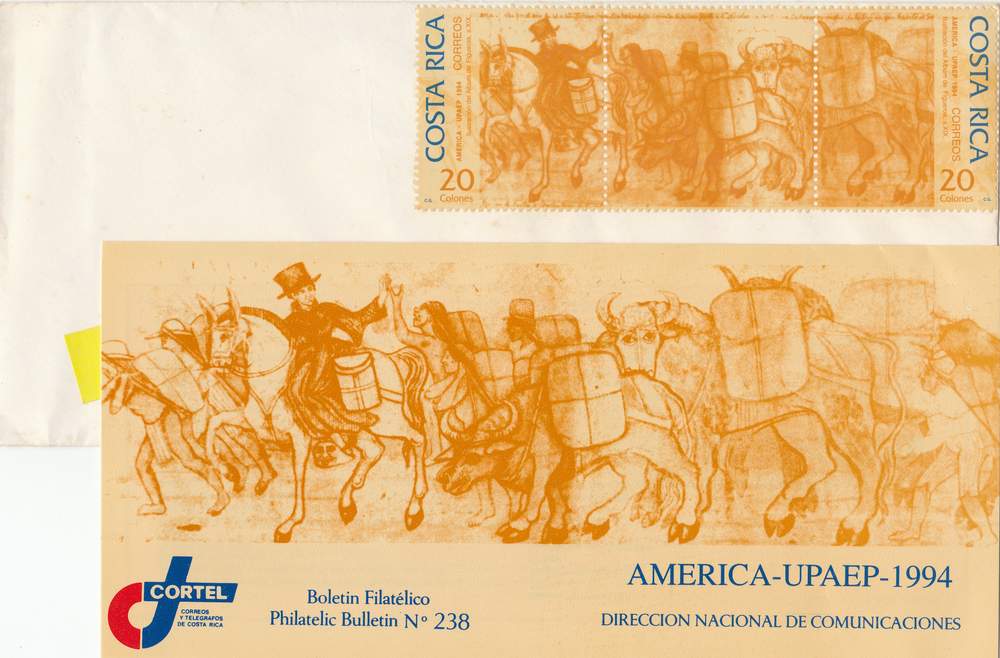

Getting the beans to the coast was a major undertaking. To transport the beans, the Costa Rican families used the carreta típica or oxcart. Oxen were the most reliable animals for the steep slopes and slippery soils of the highlands. Usually several families would form a convoy of carts to transport the coffee to Puntarenas, where sailing ships loaded with the beans headed for Valparaiso, Chile. From there merchants transshipped the beans to Europe, mainly England. Some of the old unpaved oxcart tracks are still in use today, although heavy rains erode some sections every year to look like creeks. One large unpaved section still exists between Piedades de Santa Ana and Cuidad Colón. It was part of the long track via the towns and villages of Puriscal, San Pablo, San Pedro, Orotina, ending in Puntarenas. In later years, the government organized the paving of the steep parts of the main track with cobble stones and the construction of bridges over the river canyons. One original paved section still exists, running west from the town of Atenas to San Pablo and San Pedro. That paved road became the main road for all transportation to and from the coast. In La Garita, just before the hydroelectric dam in the canyon of the Rio Grande River, a sign indicates where the old custom house used to be located. Here, early governments charged duties on outgoing and incoming goods. On the Atenas side of the

Rio Grande River, the old oxcart road is now paved with asphalt, and where the road meets the modern highway, the municipality erected a commemorative statue of a boyero and his oxcart.

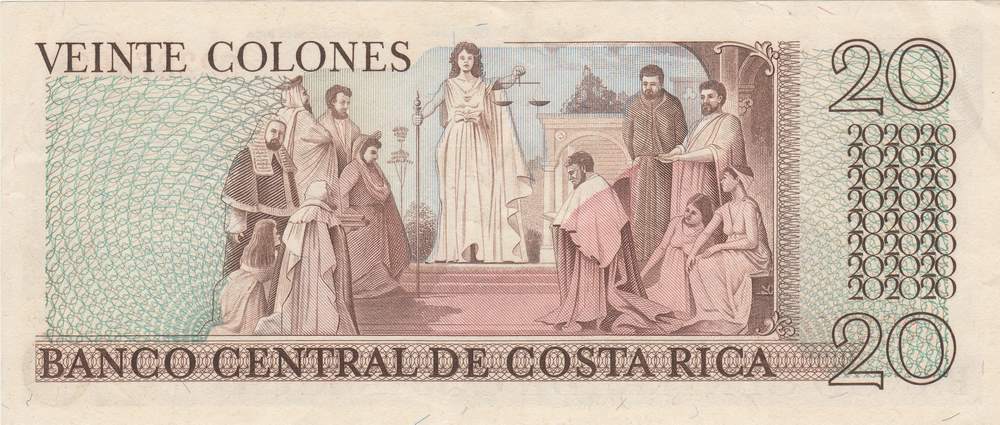

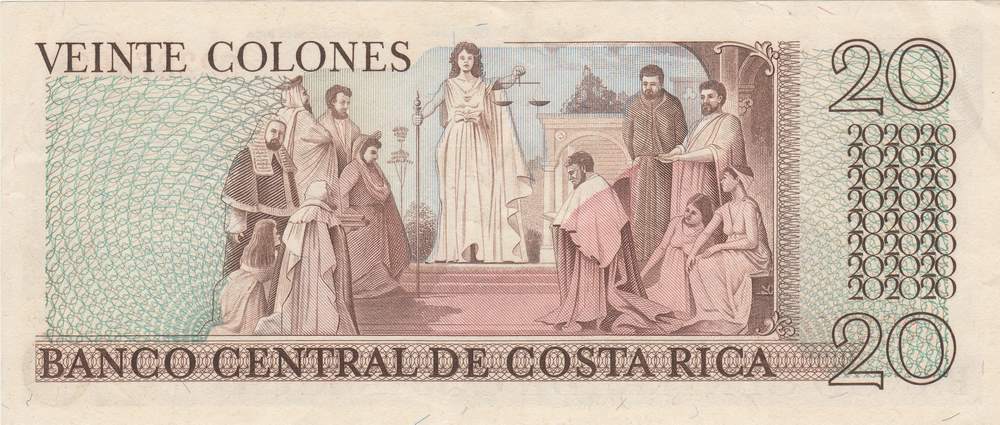

Costa Ricans were surprised to find (a month after the fact) that Central America had become independent in September of the year 1821. It led to the formation in 1823 of the United Provinces of Central America. Its organization was based on the model of the United States. The coat of arms adopted by the new state reflected their wish to develop a modern democratic nation: depicted in the center was the Phrygian cap, shining its beams of enlightenment of the French revolution over the five countries depicted as five mountains between two oceans. During the two years before the Federal States started to function, the four independent major towns in Costa Rica became divided between the monarchists (majorities in Cartago and Heredia) and the republicans (majorities in San José and Alajuela). By 1824 the colonial title of governor was renamed Jefe de Estado. In 1838 the United Provinces of Central America ceased to meet and therefore to exist. Costa Rica found itself, by default, an independent country, without having formal governmental institutions.

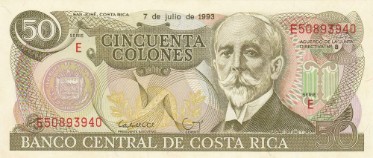

Most historians and social scientists agree that the basic egalitarian democratic attitudes of the Costa Rican populace originated during the period of agricultural self-sufficient farming, when kinship cooperation permeated all of society. Isolated from the outside world and with no internal threats from underprivileged groups, a largely egalitarian society had emerged in which dialogue and compromise led to a broad consensus. Coffee became the primary trade item enabling the importation of metal tools and cloth. Coffee seeds and plants were distributed among the families who wanted them. This was in addition to the free land still available during the early years of independence. The clearing of the land had to be done by the family itself. Coffee production increased dramatically after 1838, and by 1848 when Costa Rica officially declared itself a republic, the majority of the population owned their land, houses and some tools, and were producing coffee for export.

With the lack of outside threats, the country had no standing army. When an outside threat appeared in the form of William Walker, an American who intended to conquer and subdue the Central American countries into slave states, the Costa Rican men responded eagerly to defend their freedoms and flourishing economy with minimal weaponry. The mercenaries of Walker were stopped before they even came close to the Central Valley. This violent encounter produced Costa Rica’s only recognized war hero, a young man from Alajuela, Juan Santamaria. Although several men died during the fighting, including Juan, the real destruction of lives took place when the men returned home infected with cholera. Within a year Costa Rica lost up to 10% of its population. After the cholera epidemic diminished, coffee production went into a period of explosive growth and in the years from 1850 to 1890 it formed 90% of the value of the exported products of the country.

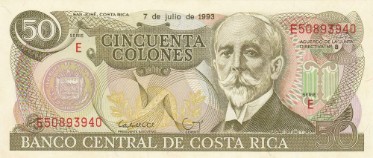

During that period the population more then doubled. Wealth differences started to appear between families; some accumulating more and more land, including land located outside the Central Valley, where most of the labor was performed by hired peones. Cooperatives became a popular organization for many smaller coffee farmers, but some small land holders preferred to sell their crops to the larger land holders, who became known as cafetaleros. These transactions did not involve money, but private tokens known as boletas de café.

When traditional inheritance rules were followed upon the death of a cafatelero, the land and coffee operation would be inherited by the eldest son, with stipulations that he would look after the other siblings. Those siblings increasingly preferred to become merchants, teachers, doctors, dentists or lawyers. At the same time these more intellectually inclined individuals started to become interested in organizing the country along the lines of a modern state.

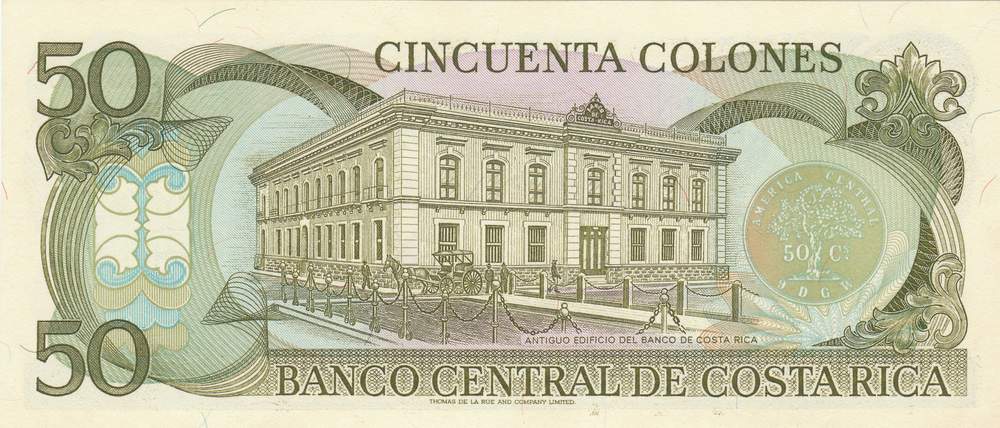

The wealthy families were never a homogeneous group. There were the Church-oriented conservatives and science-oriented liberals. Those who did not inherit land and became urban, educated specialists, often formed a community of idealistic liberals who involved themselves in politics to introduce democratic ideas. During the years from 1870 to 1900, several liberal presidents were able to introduce free, compulsory, civil primary education, civil registries of births, deaths and marriages, abolish the death penalty and establish the National Theater. They were anti-clerical, accusing the Church of not properly educating and civilizing the people, but keeping them backward and superstitious. In 1888, they forced the Catholic University of St. Thomas to close, but they allowed the schools of law, agronomy, fine arts and pharmacy to operate independently.

The First World War gave some politicians the idea that an army was needed to protect Costa Rica from the threat of communism. In 1917 the government began the construction of a fortress in San José where young men were supposed to be trained to become soldiers. It received the pretty name of Cuartel Bellavista. They did not finish the construction until the early 1930’s. By then the Depression in the industrialized world caused a devastating downturn in the coffee market, which was shortly thereafter followed by the almost total collapse of the coffee trade during the Second World War. The decline of income of both the population and its government prevented a proper army from being developed. The Cuartel Bellavista did play a passive but important role after all in 1948, when José Figuerres ceremoniously attacked and destroyed a section of the wall with a sledgehammer to symbolically celebrate the official abolition of a standing army in Costa Rica. The following year the legislative assembly codified the prohibition of any form of military organization in the constitution. They also rededicated Cuartel Bellavista as the Museo Nacional. The outside walls of the building still today show the scars of the bullet damage of the short but crucial civil upheaval in 1948 that established Costa Rica as the first as well as the largest country in the world without a standing military force.

Today, the country is not without a protective shield: there are several police organizations, as well as a secret service, all keeping an eye on the safety of the population. Almost all governments since 1948 have introduced laws that safeguard democracy for all citizens, regardless of gender or race. For many years the government was also the dominant economic force in the country, providing the majority of jobs. Many of those jobs were in education and health, ensuring Costa Ricans better living conditions than most other Latin American countries. During the last 10 years the economy has boomed due to a variety of international companies establishing administrative offices and light industries in the country. They were attracted by the peaceful conditions and the well educated work force whose salaries were much lower than in the industrialized world.

Coffee no longer ranks number one on the list of exported items. Industrial products, especially microprocessors and electrical cables, took first place in 2010, accounting for 75% of exported values. The main agricultural products—bananas, pineapple, sugar and coffee—still are important, accounting for 23% of exported values. Fish and livestock products account for the remaining 2%.